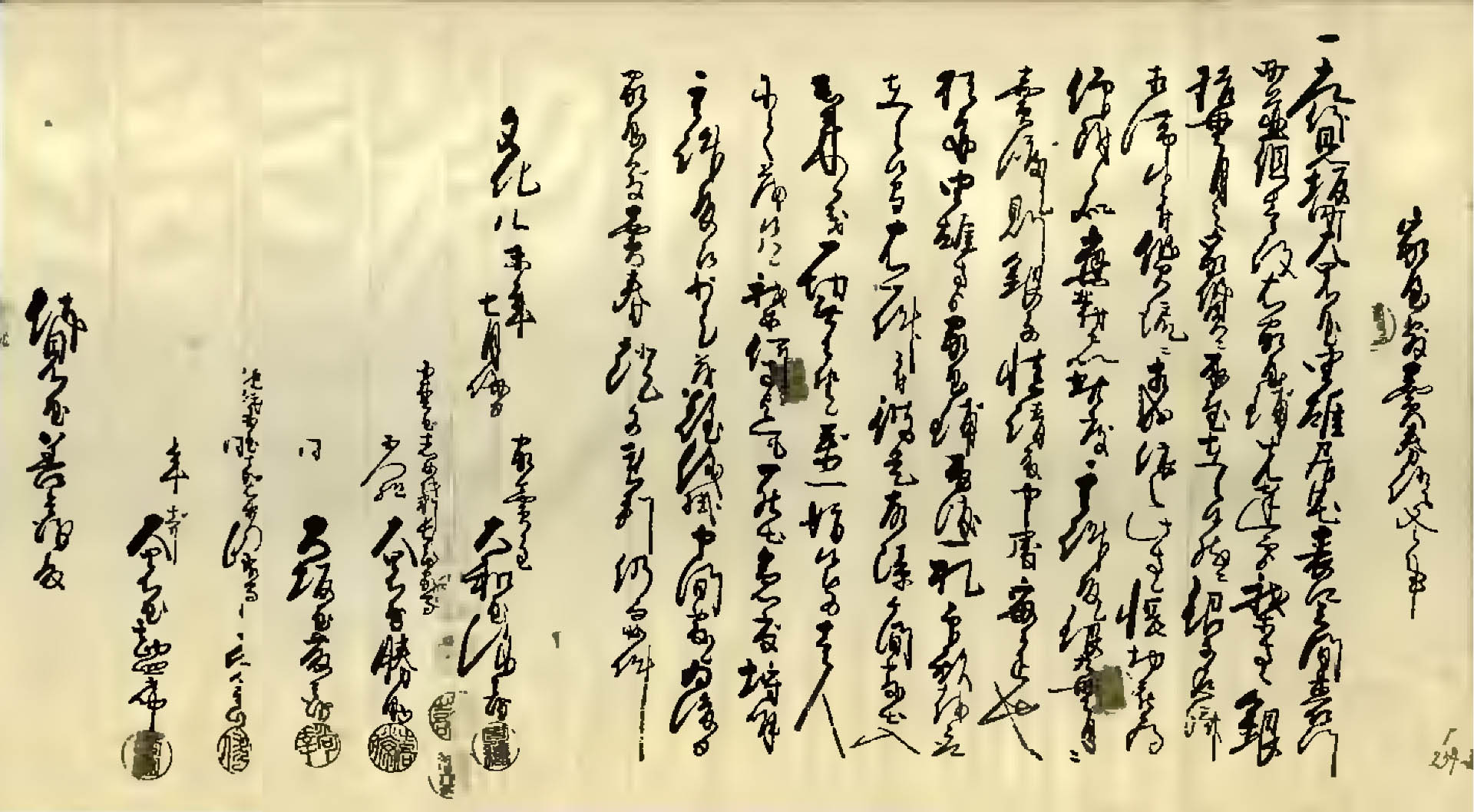

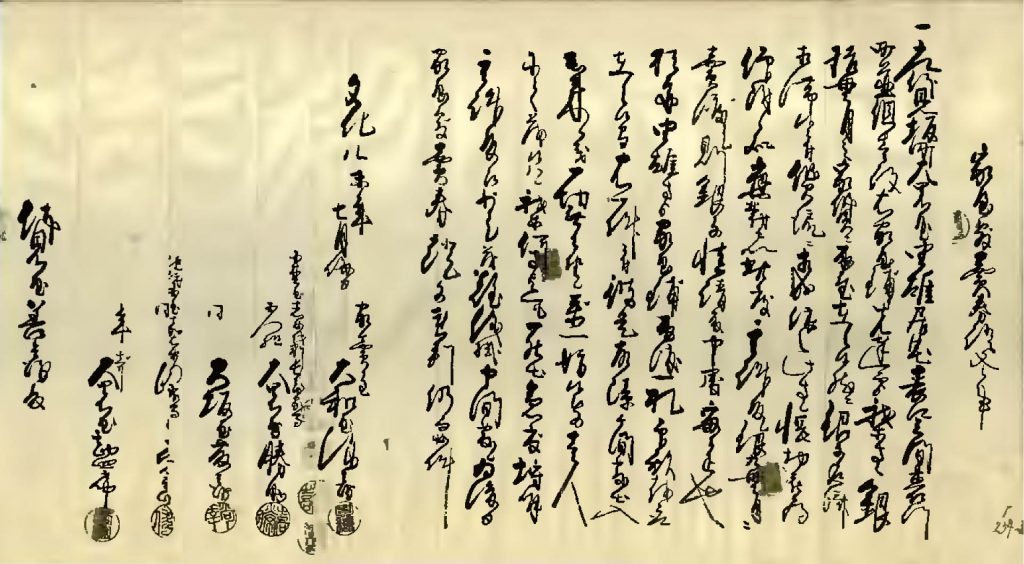

owned by Osaka City University

【Transcription and Phonetic Transcription】

家屋敷売券証文之事

一、元伏見坂町大黒屋由雄居宅、表口三間裏行

町並、但壱役、右家屋鋪、先達而ゟ

我等方へ銀

拾貫目之家質ニ取置在之候、然ニ銀子返済

相滞候ニ付、質流ニ相成、依之此方へ帳切被為

仰付候処、応対を以、此度其許殿へ銀九貫目ニ

売渡シ、則銀子慥請取申処実正也、

猶亦由雄方ゟ家屋鋪取渡一札印形を取

在之候間、右一件ニ付、彼是故障ヶ間敷出入

出来候儀、一切無御座候、万一妨候もの壱人

にても候ハヽ、我等何方迄も罷出、急度埒明、

其許殿江少しも難儀掛申間敷候、為後日

家屋敷売券証文連判、仍而如件

文化八未年七月晦日 家売主 大和屋弥兵衛

小松屋しめ代判長兵衛家守

五人組 大黒屋勝助

同 大坂屋藤兵衛

紀伊国屋嘉右衛門家守

同 嶋屋喜右衛門

年寄 大黒屋勘四郎

伏見屋善兵衛殿

【Translation】

Residential Sales Contract

Item. Previously, I [Yamatoya Yahē] accepted Daikokuya Yoshio’s residential property in Motofushimisakamachi, which has a frontage of three ken, a depth equivalent to the lots surrounding it, and an associated tax levy of one ken, as collateral for a loan of ten kanme of silver. However, Daikokuya was forced to forfeit ownership of the property because he failed to fully repay the loan. Thereafter, on the order of the City Governor’s Office, my name was added to the chō land register as the property’s owner. However, I officially acknowledge that we then reached an agreement under which I sold the estate to you [Fushimiya Zenbē] in exchange for nine kanme of silver. Furthermore, there will be no future objections or disputes regarding this transaction because I also obtained a sealed acknowledgement of sale from the property’s original owner, Daikokuya Yoshio. In the rare event that even a single person attempts to interfere, I will, without fail, go to wherever the dispute is taking place and help to resolve it. By doing so, I will avoid causing you any trouble or concern. For future reference, the reasons that my guarantors and I are co-sealing this contract are as indicated above.

【Key Terms and Phrases】

Motofushimisakamachi (元伏見坂町)… A chō located on the southern side of Osaka’s Dōton Canal / Kyotaku ( 居宅)… A residential lot and domicile/Urayuki machinami (裏行町並)… This phrase indicates that the depth of the residential plot in question is the same as those around it. / Warera (我等)… Although the term warera usually indicates multiple persons, in this case, it refers to a single person. / Gin jūkanme (銀拾貫目) … Ten kanme of silver. One ryō of gold is equivalent to 60 me of silver, and one kanme is worth 1000 me, so ten kanme of silver is worth approximately 170 ryō. / Kajichi (家質)… A loan provided to a person who puts up a residential property as collateral / Shichi nagare (質流れ)… The transfer of the right of ownership of a property that was put up as collateral in exchange for a loan that the recipient failed to repay on time / Chōgiri oosetsukesaserare (帳切仰付けさせられ)This phrase can be translated, “The City Governor’s Office has ordered that the land register (水帳) be amended.” It indicates that a suit was likely filed with the City Governor’s Office after the loan recipient fell into arrears. / Ōtai (応対)… Negotiation or consultation / Soko moto(其許)… An honorific expression meaning “you” / Jisshō (実正)… An expression meaning “certainly” or “without a doubt” / Ieyashiki toriwatashi issatsu (家屋敷取渡一札)… A written agreement or contract in which one party pledges to transfer ownership of a residential lot and domicile to another party / Kare kore (彼 是)… This or that; one or another / Koshōgamashiki (故障ヶ間敷)…An adjective meaning “obstructive” / Deiri(出入) … A dispute/Shuttai (出来)… The occurrence of an event or incident /Kitto (急度)… A phrase meaning “without fail” / Rachiake (埒明) The resolution of a dispute or problem / Nangi (難儀)… Trouble or annoyance

【Explanation】

This is a residential sales contract that was composed on the final day of the seventh month of Bunka 8 (1811) when Yamatoya Yahē sold a house and residential lot occupied by Motofushimisakamachi resident Daikokuya Yoshio to Fushimiya Zenbē, another Motofushimisakamachi resident.* Daikokuya was the property’s original owner. The use of the term kyotaku, which can refer to a person’s current place of residence, indicates that Daikokuya was still living on the property at the time of the sale. When Daikokuya Yoshio borrowed money from Yamatoya Yahē, he put up his house and lot as collateral. However, the property was forfeited and ownership was transferred to Yamatoya, because Daikokuya failed to repay his loan. Although Yamatoya accepted Daikokuya’s property as collateral, the fact that he quickly sold it to Fushimiya Zenbē after assuming ownership indicates that Yamatoya either had no use for the house and lot or wanted cash rather than property. Yamatoya lent ten kanme of silver to Daikokuya and sold Daikokuya’s estate to Fushimiya for one kanme of silver. Therefore, if we suppose that Daikokuya failed to repay any of his debt to Yamatoya, then Yamatoya suffered a loss of one kanme of silver. (However, it is likely that Daikokuya paid a part of his debt Yamatoya. Therefore, it is hard to believe that Daikokuya’s debt to Yamatoya was any larger than nine kanme.) Regardless, Yamatoya likely wanted cash even if he was forced to suffer a small loss.

This is also an interesting example of a residential property that was put up as collateral and eventually forfeited.

The property in question was located in Motofushimisakamachi, the chō in which the buyer, Fushimiya Zenbē, also resided. Motofushimisakamachi was located just south of the Dōton Canal and was a neighborhood in which teahouses (chaya) were officially permitted to operate.

*(Fushimiya Zenbē: Fushimiya Zenbē moved to Motofushimisakamachi in the nineteenth century after purchasing an estate there. While living in the chō, he operated a teahouse. He also owned a pawnshop and used his wealth to fund theatrical performances. The Fushimiya Zenbē House also engaged in money lending activities, which sometimes involved the use of residential properties as collateral. As the above example indicates, there were cases in which a loan recipient fell into arrears and forfeited their homes and lots to Fushimiya. The properties owned by Fushimiya were concentrated in Osaka’s Shimanouchi district and in neighborhoods in which teahouses were permitted to operate.

In addition to the seller, the chōdoshiyori (the chō headman), and the members of the seller’s goningumi (Five-Household Association) sealed the above contract. At the time that the document was composed, the chōdoshiyori and members of the seller’s goningumi were required to approve and seal all residential sales contracts. Let us examine the development of early modern procedures governing the exchange of residential properties.

From the early 1580s, when a property was sold, the buyer and seller were required to pay a registration fee (chōgirigin) equivalent to one-fortieth of the total sale price to the authority within whose domain the property was located. In the case of Osaka, such fees were paid to the City Governor’s Office. Upon receiving a registration fee, the City Governor’s Office issued written receipts to the buyer and seller. Several such receipts have been preserved. The next major development in the procedures surrounding property sales came during the late Tenshō period (1573-1592). In Tenma Jinaimachi, an urbanized community that developed in the late-sixteenth century around Hongan Temple, both the Land Steward (jibugyō) and City Governor (machibugyō) began to conduct thorough inspections of all property sales. For that reason, the written receipts issued by the City Governor expressed both public recognition of a property transaction that had already been approved by the headman in the chō where the property was located and served as an official acknowledgement that a property registration fee had been collected.

The third major development came in Kan’ei 11 (1634) at the time of Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu’s visit to Osaka. In that year, Iemitsu exempted the entire city of Osaka from land taxes. At the same time, the city authorities increased the property registration fee from one-fortieth to one-twentieth of a property’s total sale price. However, those fees were now to be paid directly to the chō where the transaction took place and shared by the chō’s constituents. As a result of those changes, the format of residential sales contracts also changed.

An official proclamation issued on the 23rd day of the fifth month of Kan’ei 17 (1640) states, “Regarding the buying and selling of residential properties, properties may only be bought or sold after informing the headman and members of the five-household association in the chō in which the property is located. For example, even when there is a sales contract, if the sale has taken place without the permission of the chō, matters relating to the property’s ownership and disposal cannot be determined through official adjudication.” Therefore, in order to buy or sell a residential property during the early modern period, it was necessary to first obtain the consent of the headman and five-household association in the chō where the property was located. In addition, a subsequent proclamation issued on fifth day of the fourth month of Keian 1 (1648) states, “Regarding the buying and selling of residential properties, a sale must be concluded only after consulting with the headman and five-household association in the chō where the property is located. For example, even if there is a sales contract, if the headman and members of the five-household association have not affixed their seals, the contract shall not be recognized as valid.” In other words, the proclamation issued in Keian 1 mandated that the headman and members of the five-household association of which the property was part approve and seal all sales contracts. Based on the above rules, a residential sales contract only became valid after the headman and members of the five-household association had affixed their seals. Once sealed, such contracts maintained their validity even if a dispute occurred and the property became the focus of an official suit at the City Governor’s Office.