Preface

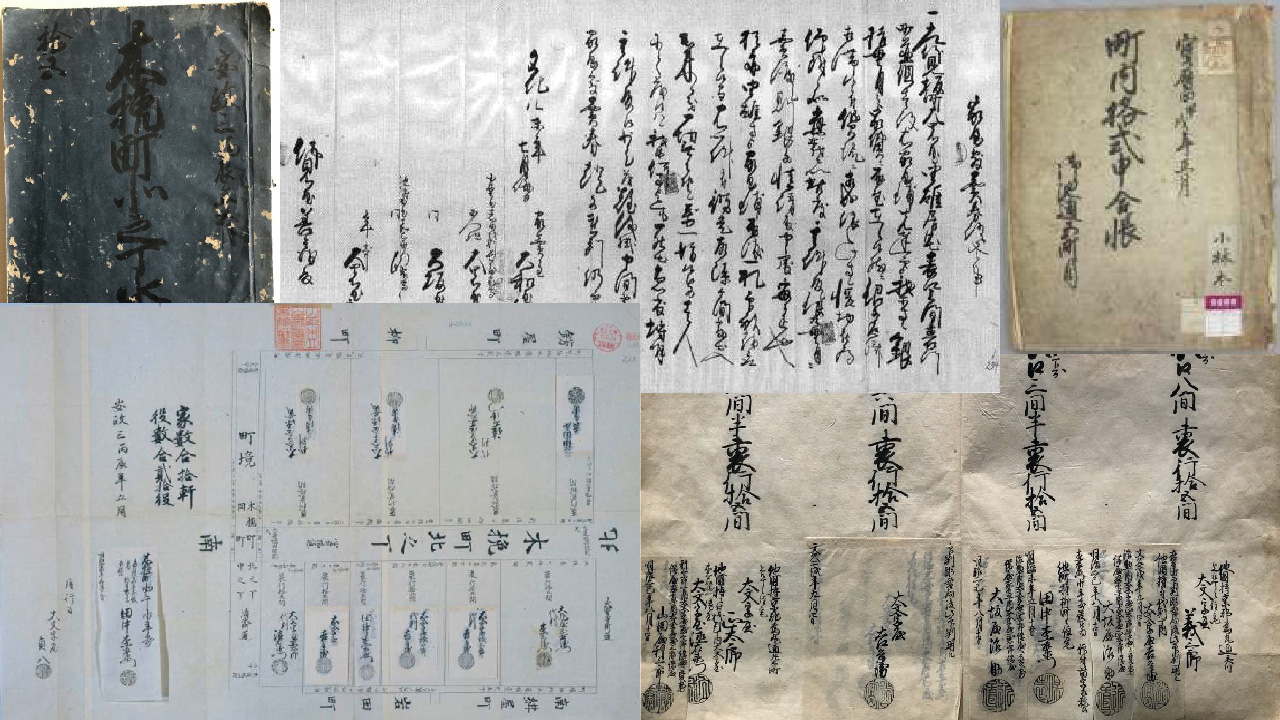

This volume is based on a pair of Japanese-language texts composed in 2010 and 2011 as part of the Osaka City University Urban Problems Research Center project, “Historical Conceptions of Early Modern Osaka and the Development of Documentary Texts.” The Japanese texts are entitled Shiryō kara yomu Ōsaka no rekishi: kiso hen, shikōbanⅠ (The History of Osaka from the Documents, Basic Edition, Trial Volume Ⅰ) and Shiryō kara yomu kinsei Ōsaka: shikōban Ⅱ (Early Modern Osaka from the Documents, Trial Volume Ⅱ). The texts were composed with the intention of producing a series of volumes that utilize archival documents to empirically examine Osaka’s early modern history. They were written primarily for Japanese history students and domestic visitors to the Osaka History Museum. In contrast, this volume is intended specifically for non-native researchers interested in Japanese history. Additionally, we hope that foreign visitors to Japan who develop an interest in Japanese history will engage with and learn from the text.

The city of Osaka possesses a rich historical legacy. When attempting to elucidate that legacy, it is vital to examine its deep structural currents rather than focusing on its surface features. Accordingly, a historical consciousness, which recognizes the distinct character of each historical era, is essential. The most effective way to examine history’s deep currents is to engage directly with the primary sources, which directly convey the spirit and vitality of the people of each historical era. In recent years, Japanese researchers have had increased opportunity to interact with foreign scholars of Japanese history. A number of those scholars have conducted original research utilizing primary sources and produced significant results. This volume is designed as a text that foreign researchers can use in their history courses. At the same time, it is also intended for the many foreign tourists who visit Japanese history museums each year and view the exhibits. We hope that this text will help to convey to such individuals the utility and value of examining history from the primary sources.

Osaka City University professor Tsukada Takashi and Osaka Museum of History curator Yagi Shigeru prepared the original Japanese content upon which this volume is based. Tokyo University of Foreign Studies associate professor John Porter and Allegheny College visiting assistant professor Matthew Mitchell translated the Japanese content into English.

★As shown below, we will post this volume in ten parts.

Contents

| Lecture 1 | The Urban History of Osaka |

| Lecture 2 | An Overview of Early Modern Osaka’s History |

| Lecture 3 | The Chō—The Basic Unit of Urban Residential Life in Early Modern Osaka, An Introduction |

| Lecture 4 | 《Document Reading #A》 Cadastral Map (Kobikimachi-kitanochō Cadastral Map) ① |

| Lecture 5 | 《Document Reading #A》 Cadastral Map (Kobikimachi-kitanochō Cadastral Map) ② |

| Lecture 6 | 《Document Reading #B》 Residential Sales Contract |

| Lecture 7 | 《Document Reading #C》 A Register of Rules and Agreements for the Miike dōri 5-chōme Neighborhood Association ① |

| Lecture 8 | 《Document Reading #C》 A Register of Rules and Agreements for the Miike dōri 5-chōme Neighborhood Association ② |

| Lecture 9 | 《Document Reading #C》 A Register of Rules and Agreements for the Miike dōri 5-chōme Neighborhood Association ③ |

| Lecture 10 | Conclusion |

Lecture 1 : The Urban History of Osaka

Although the origins of the contemporary city of Osaka can be traced to Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s construction of Osaka Castle and the surrounding castle town in 1583, the earliest urban settlements in the Osaka region actually date back as far as the fifth century.

The Pre-Classical Era

During the Jōmon era (14,000 BC-300 BC), Osaka Bay extended much further inland than it does today. During that period, the Uemachi Plateau jutted out into the ocean, forming a peninsula. Over time, however, the sea level receded and silt from the Yodo and Yamato River systems began to accumulate in Osaka Bay. That silt was then carried inland from the Bay, eventually collecting in areas previously underwater on the eastern and western sides of the Uemachi Plateau.

This region came to be called Naniwa. Located at the eastern edge of the Seto Inland Sea, Naniwa became a key transit point linking the Kinki Region with Western Japan, China, and the Korean Peninsula. Until the fifth century, a confederate chieftain, who united all of the region’s local headmen, ruled Naniwa. However, during the sixth century, an imperial clan based in the Nara Basin drove out Naniwa’s confederate chieftain and established control over the region. In addition, during the fifth century, a port known as Naniwanotsu and various political and economic institutions were constructed in the region. In the sixth and seventh centuries, envoys from the various kingdoms on the Korean peninsula, including Goguryeo(高句麗), Baekje(百済), and Silla(新羅), traveled frequently to the Japanese archipelago. In such instances, Naniwatsu served as a national port.

Naniwanomiya

According to the Nihon shoki (The Chronicles of Japan), in the twelfth month of 645, shortly after the Taika Reforms, Emperor Kōtoku moved the imperial capital from Nara’s Asuka region to Naniwa’s Nagara-Toyosaki region. During the late 640s, construction began on an imperial palace. Completed in the ninth month of 652, the Nihon shoki described it as a palace so grand “that it was beyond description.” When Emperor Kōtoku died in 654, the imperial capital was swiftly returned to the Asuka region. Despite that fact, the palace that Kōtoku constructed in Naniwa remained in place until it burned down in 686 during the reign of Emperor Tenmu.

Although Naniwanomiya Palace was not immediately reconstructed, efforts were initiated to rebuild it in 726. In 744, after the Palace was completed, Emperor Shomu moved the capital back to Naniwanomiya for a short time. However, it was quickly relocated to Heijokyō in present-day Nara City. Then, in 784, when the imperial capital was moved from Heijokyō to Nagaokakyō, Naniwanomiya Palace was dismantled and moved from Naniwa to Nagaokakyō. As a result, the imperial palace and Naniwanomiya city area ceased to exist.

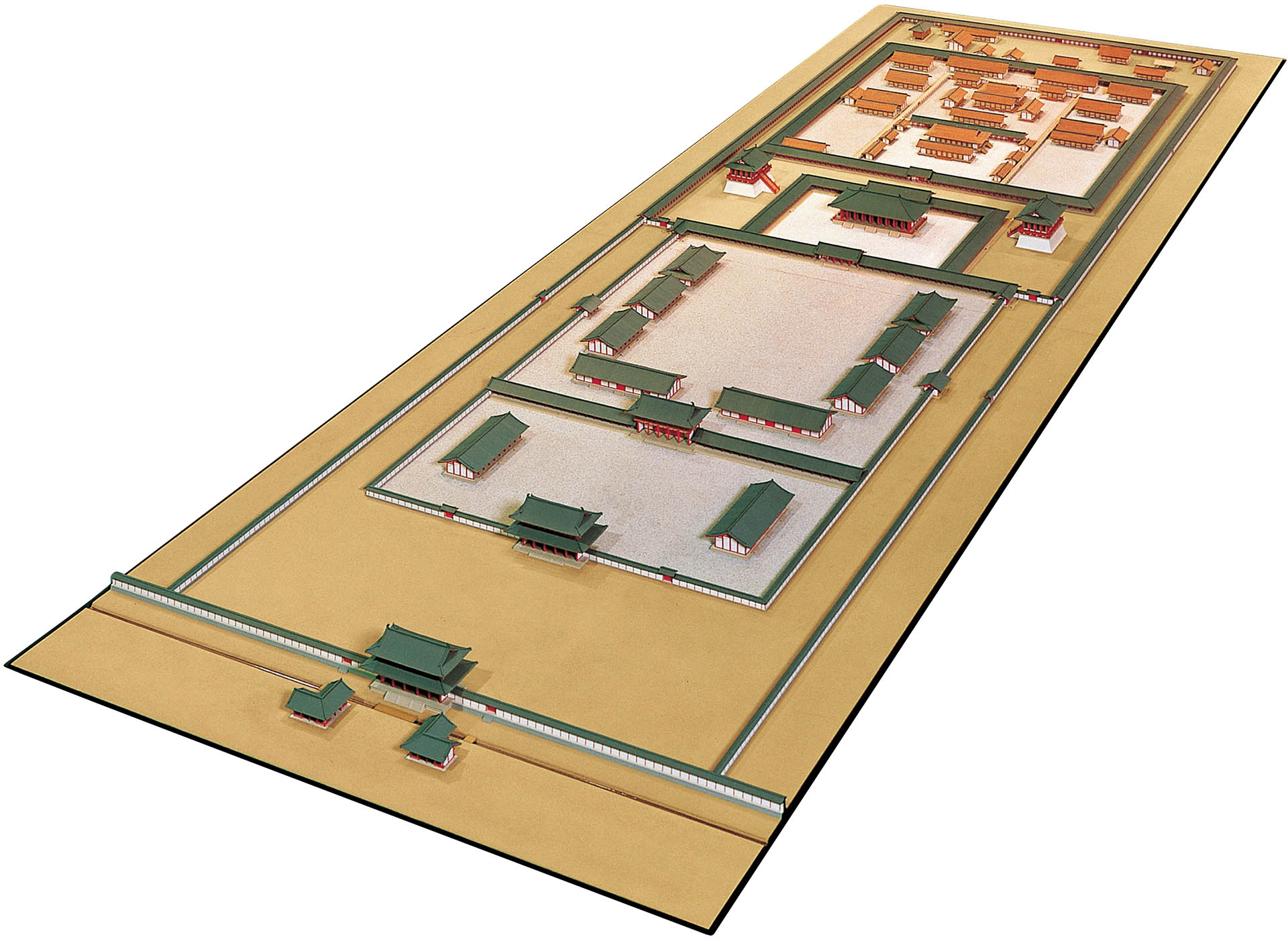

Property of the Osaka Museum of History

In the seventh and eighth centuries, therefore, an imperial capital known as Naniwanomiya existed in the Naniwa region.

The imperial capitals constructed during this period were modeled on China’s ancient capitals. Unlike China’s urban capitals, however, Japan’s imperial capital cities were not walled. Yet, as in China, emperors lived in and conducted their political affairs from a central palace, which was surrounded by an urban settlement that was arranged in a chessboard-like grid. In the case of Naniwanomiya, archaeological evidence confirms the existence of a central palace. While it is believed that there was also a surrounding city area, its physical appearance and internal structure are unknown.

The focal point of the Naniwa region was the imperial capital at Naniwanomiya. During the period in question, the region was the site of three intersecting “worlds”: the world that developed in the rural districts surrounding the capital, which centered on the various influential clans that held sway in Naniwa during the sixth century, the world of the capital, which was laid out in a chessboard-like pattern and populated by the emperor’s vassals, and the world of the national port at Naniwanotsu, which was a thriving center of trade and arriving tribute from western Japan, and the location from which Japanese envoys bound for the Asian continent departed.

Classical and Medieval Cities

In 794, the imperial capital was moved from Nagaokakyō to Heiankyō. In 788, just six years before the capital was relocated, Naniwanomiya was officially disbanded. In addition, the region lost its role as a capital city and national port as a result of the development of alternative river transportation routes and the abolition of the foreign envoy system.

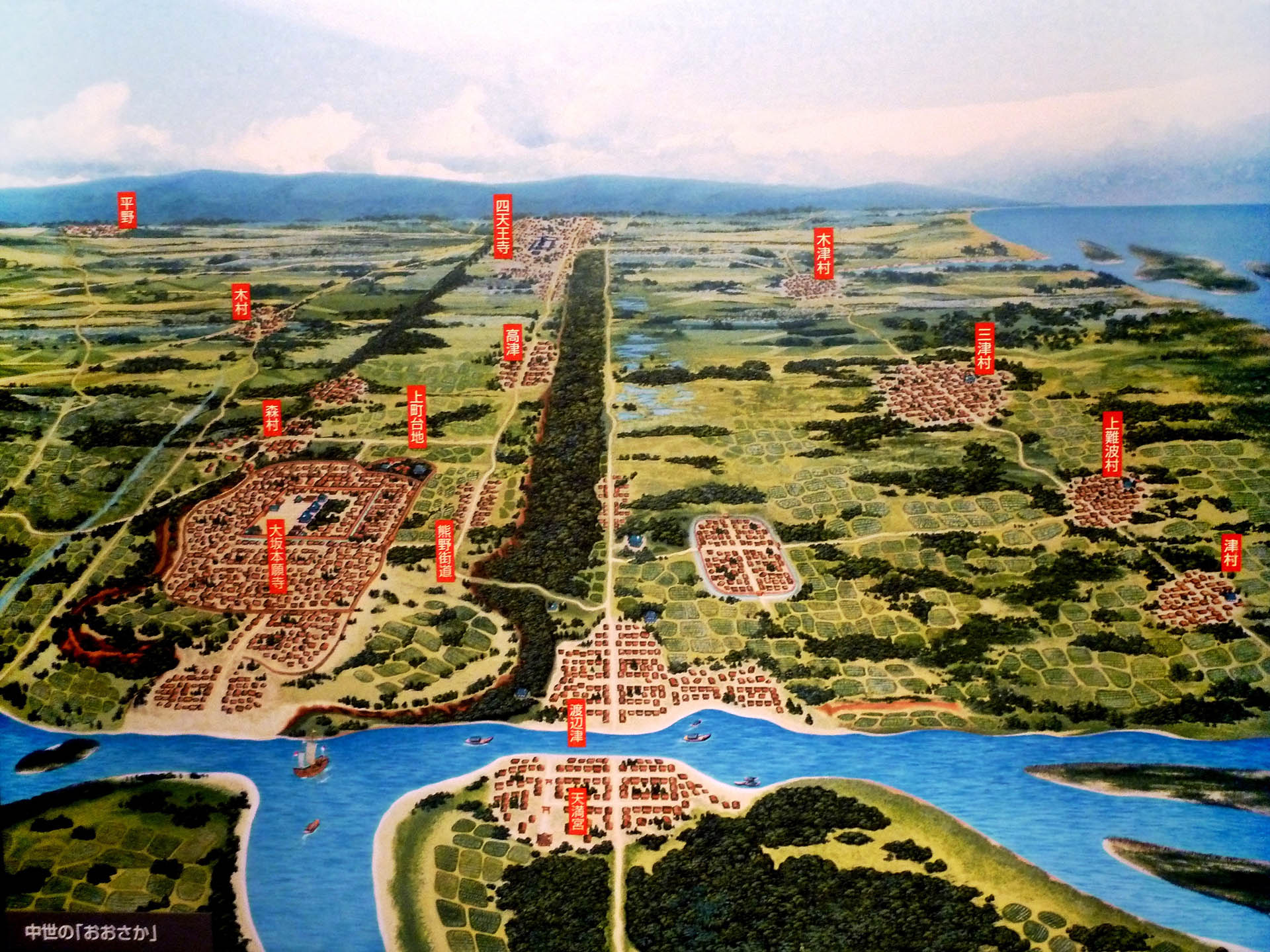

During the medieval period, an urbanized settlement developed at Watanabenotsu, the regional port that succeeded Naniwanotsu. A warrior band known as the Watanabe-to ruled Watanabenotsu. In addition, Watanabenotsu marked the point of origin of the Kumano Road. It was a sizable port city and hub of river traffic. However, when compared with Naniwanotsu, which served as both a national capital and port, Watanabenotsu was little more than a regional center. During the late-medieval period, a second urbanized settlement developed in the vicinity of Shitennō Temple. At the same time, the Sakai area, which was located further south, saw the development of a major international port.

Property of the Osaka Museum of History

The Osaka Hongan Temple Settlement

In addition to the above areas, it is also essential to mention the urbanized settlement that formed around Osaka’s Hongan Temple. The origins of the Hongan Temple settlement can be traced to 1496, when Rennyo, the head of the True Pure Land Buddhist sect, established a retreat in an area known as Osaka. The place name “Osaka,” which literally translates as “large slope,” is believed to refer to a broad slope on the western side of the Uemachi Plateau. From 1531, the year that Hongan Temple, the head temple of the True Pure Land sect, was moved from Yamashina to Osaka, until 1580, the year that the Temple was driven from the area following the conclusion of the Battle of Ishiyama with Oda Nobunaga, Osaka developed rapidly as an urbanized settlement surrounding Hongan Temple.

Property of the Osaka Museum of History

As described below, in 1583, Toyotomi Hideyoshi initiated the construction of a castle on the former site of the Osaka Hongan Temple Settlement. Hideyoshi’s initial plan called for the construction of a linear urban settlement on top of the Uemachi Plateau, which would extend southward to Shitennō Temple and onward to Sakai. His plan was modeled on a series of cities constructed elsewhere in Japan during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Osaka Hongan

Temple settlement was important not only because it served as the site for Osaka Castle, but also because it was “home” to an early modern-style urban community, which was populated by commoners who owned their own land parcels. That community came to serve as a model for Osaka’s subsequent urban development. In that sense, it played a vital role in the making of early modern Osaka.

Imperial Capitals and Castle Towns

Early modern Osaka’s basic structure was that of a castle town, which had Osaka Castle as its locus. As mentioned above, the origins of the contemporary city of Osaka can be traced to the castle town that emerged during the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth centuries. The early modern city of Osaka is the primary focus of this book. Accordingly, it will be examined in detail in the following section.

Yoshida Nobuyuki has hypothesized that the historical development of cities can be broken into three stages: the traditional city stage, the modern city stage, and the contemporary city stage. For Yoshida, the term “traditional city” (dentō toshi) refers to the diverse array of pre-modern urban models that existed before capitalism emerged as the world’s dominant mode of production. Although there were many kinds of traditional cities, traditional cities in Japan can be divided into two primary types: imperial capitals (tojō) and castle towns (jōkamachi). Imperial capitals based on urban models imported from China were the dominant form of urban settlement from the classical period until the early stages of the medieval period. However, during the fourteenth century, they began to fade from existence. In contrast, the castle town was an urban model that was unique to pre-modern Japanese society and one that significantly influenced the development of modern cities in Japan.

In summary, in pre-modern Osaka (Naniwa), two types of cities—imperial capitals and castle towns—emerged in chronological succession. In that sense, Osaka represents a model example of Yoshida’s hypothesis about the dominant models of pre-modern Japanese urban development.

Modern and Contemporary Osaka

Lastly, let us briefly examine the transformation of early modern Osaka into a modern and then contemporary city. According to Yoshida Nobuyuki’s aforementioned urban development hypothesis, “contemporary cities” (gendai toshi) are characterized by increasing standardization and homogenization resulting from the process of globalization. In contrast, “the modern city” (kindai toshi) represents a transitional or intermediate urban type that emerged amidst the disintegration and transformation of traditional society resulting from the industrialization process.

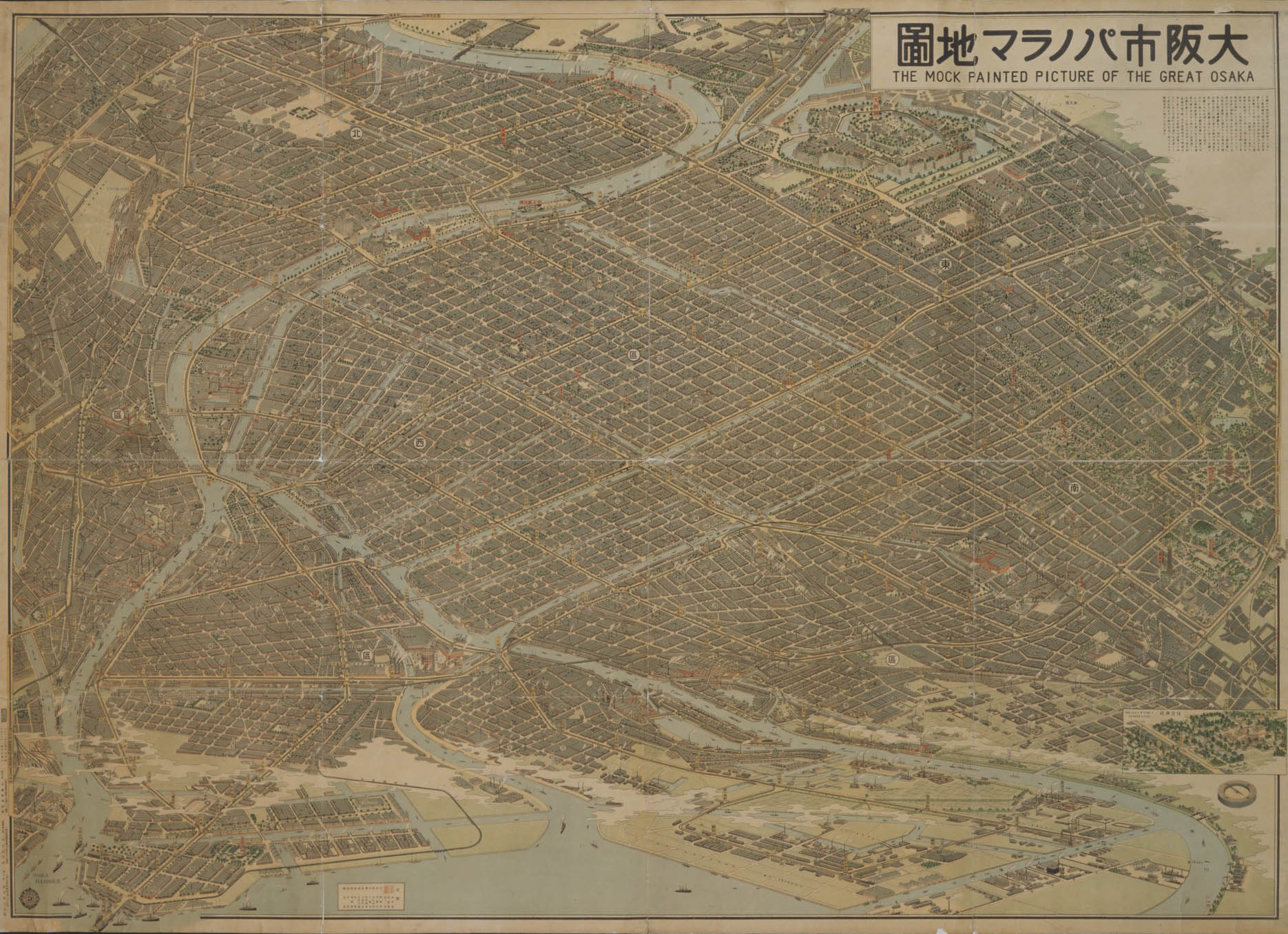

Following the Battle of Fushimi Toba in January 1868, the fifteenth Tokugawa Shogun, Yoshinobu, was driven from Osaka Castle and the Edo Bakufu lost control of the city. The Meiji government then took over Osaka and through a process of trial and error overhauled the city’s political and economic institutions. Until 1888, early modern political and socio-economic organizations based on the chō (neighborhoods association) remained in existence. However, during the late 1880s, the Meiji government introduced the City, Town, and Village System (Shichōson-sei) and the school district (gakku) emerged as the basic unit of urban administration. These changes served to gradually transform the structure of local society in Osaka. In the immediate aftermath of the Meiji Restoration, Osaka’s economy stagnated as Tokugawa-era silver currency was phased out and the central government assumed responsibility for domainal debts. However, during the late 1870s and 1880s, the industrialization process began to gain momentum and a series of modern industrial enterprises, including a mint, armaments factory, textile factories, and ironworks were constructed in the vicinity of Osaka Castle and on tracts of reclaimed land on Osaka’s coast. At the same time, the city also began to undergo a process of rapid modernization, as it expanded outward and absorbed waves of new migrants. In addition, the authorities began to gradually develop the city’s infrastructure and establish its basic social institutions. However, at the same time, a new urban lower class formed as the industrialization process advanced and the city’s population expanded. In addition, industrialization and rapid population growth gave rise to a wide range of novel urban social and labor problems. Furthermore, the city area itself continued to grow. In 1925, the city limits were expanded outward for a second time in order to observe newly urbanized districts on Osaka’s margins. In the process dozens of towns and villages were subsumed into the city. At its peak, Osaka’s total population rose to more than 3,000,000. During that period, the total value of the city’s industrial output was the highest in the nation and the port of Osaka served as the nation’s leading hub for exports to Asia.

Property of the Osaka Museum of History

Much of the modern city area was destroyed during the Allied bombing raids carried out over Osaka in 1945. The city’s appearance was dramatically transformed as a result of the postwar reconstruction process and the subsequent “era of high-speed growth.” Corporate buildings began to concentrate in the city center and the city area expanded rapidly outward into surrounding communities. As a result of this process, the population of the city center decreased and the local social networks that existed there disintegrated. At present, the communal bonds once that once existed in the city have all but disappeared. While these changes cannot simply be attributed to the fact that Osaka has become “a contemporary city,” it is clear that the processes of homogenization and standardization are advancing.